Merv is one of three UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Turkmenistan and has been since 1999. It was a major oasis-city in Central Asia strategically placed on the Silk Road.

A legend exists that Alexander the Great visited the city in the 3rd century BC, but whatever the truth of that it was certainly named after him for a brief time before it became Margiana. After Alexander’s death in 323 BC Merv became the capital of the Province of Margiana which continued to exist under series of dynasties: Seleucid, Batrian, Parthian and Sassanid. During 400 years of Sassanid rule Merv was home to practioners of various religions alongside the official Sassanid Zoroastrianism, including Buddhists, Manichaeans and Christians of the Church of the East.

Around 650 AD the Arabs took over from the Sassanids and under the leadership of Qutayba Ibn Muslim they used Merv as their base to bring within their subjugation large parts of Central Asia. Next came the Abbasids under the Iranian general Abu Muslim who in 748 declared a new dynasty at Merv. Throughout the Abbasid era up to 1258 Merv remained the capital and most important city of Khorasan and functioned as one of the great cities of Muslim scholarship, although the city continued to have a substantial Christian community.

In 1221 Merv opened its gates to Tolui, son of Genghis Khan on which occasion most of the inhabitants are said to have been butchered. Some historians believe that over one million people died in the aftermath of the city’s capture, including thousands of refugees from elsewhere, making it one of the most bloody captures of a city in world history.

The city took 100 years to recover from the Mongol attack, it became part of the Ilkhanate and was constantly looted by the Chagatai Khanate. By 1380 Merv belonged to the empire of Timur [Tamerlane]. The city changed hands several times in the next few hundred years until it passed to the Khanate of Khiva in 1823. In due course the Russian Empire took over and the city was captured bloodlessly by a Russian officer named Akikanov.

There are four walled cities within the Merv complex: the oldest is Erkgala [7th century BC] which corresponds to Achaemenid Merv and is the smallest. Gawurgala [also known as Gyaur Gsla] [3rd century BC] which surrounds Erkgala comprises the Hellenistic and Sassanian City is by far the largest. The smaller Timurid city was founded a short distance to the south and is now called Abdyllahangala.

One of the highlights of Ancient Merv is the Tomb of Ahmad Sanjar which was built in 1157. Ahmad Sanjar was the sultan of the Great Seljuk Empire. The Seljuks controlled a vast area stretching from the Hindu Kush to Western Anatolia and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf. Merv was the Eastern capital of this empire from 1118 to 1153.

Sorry about the quality of this pic, but it does give you a pretty good idea of the state of the Mausoleum of Sultan Sanjar in the early 20th century long before restoration work began.

The Mausoleum of Ahmed Sanjar was burned by the Mongols when they attacked in 1221. What remains today in one of the grandest of Seljuk tombs with a simple dome of blue glazed bricks and an ambitious gallery.

Ahmad Sanjar’s Mausoleum at Merv was part of a larger complex consisting of a mosque and a palace and centered on a huge courtyard. Today apart of the Mausoleum itself only foundations and footings remain of the other buildings.

The Ahmad Sanjar Mausoleum at Ancient Merv is regarded by many as a pearl of Islamic architeture: here we see the delicate stonework and mosaics around the ambitious upper gallery of the structure. We are told that the Arabic inscription on the facade can be translated as: ‘This place is enobled by the remains of the one who was called Sultan Sandzar from the descendents of the Turks-Seljuks. The was the Alexander the Great of his time; he was the patron of scientists and poets and was accepted by the Islamic world in the state of prosperity and happiness owing to sciences and arts’.

The ceiling of the inner cupola of the dome of the Ahmad Sanjar Mausoleum: not easy to convey the impact of this lovely, understated, geometrically perfect and beautifully lit Islamic architecture designed by Mohammed ibn Atsyz from Sarakhs, just inside the border of modern Iran from Mary.

Although the Mausoleum is a hugely impressive edifice it has few major decorations and this simplicity contributes greatly to the very moving experience of visiting this 900 year old structure. Its name in Persian is ‘Dar-ul-ahira’ which means ‘The Other World’ and my experience of the tomb resonates with that name…..

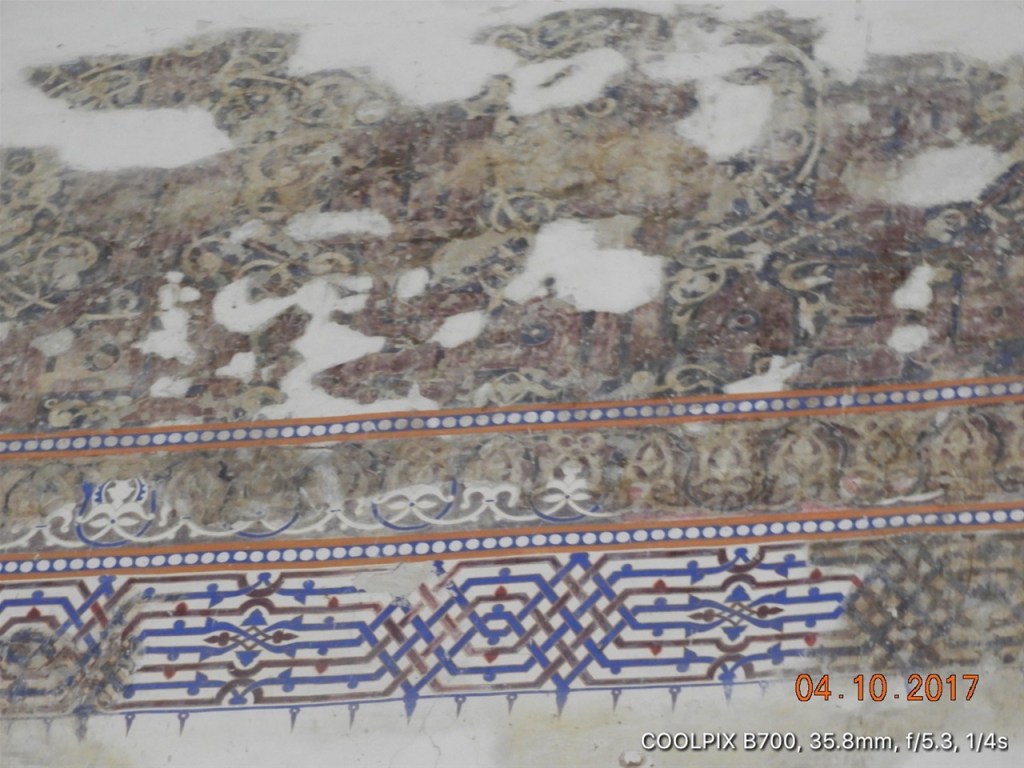

Such decoration as the Ahmad Sanjar Mausolem displays is delicate, intricate mosaic in blue and red on the white plaster.

This is the tomb of Ahmad Sanjar – it seems that today the tomb is empty, the mortal remains of Ahmad having been spirited away during the Mongol attack on the city.

More of the restoration work wihin the Tomb of Ahmad Sanjar. The Turkmen have not attempted to ‘colour in’ those areas where the mosaics are incomplete but simply left white plaster in place. Mostly i prefer this to the more Disney like approach in other countries where restorers have attempted to replicate the original mosaic with modern paintwork.

Traditionally dressed Turkmen ladies and their children visiting the Tomb of Sultan Ahmad Sanjar at Ancient Merv.

One of the buildings ancilliary to the Ahmad Sanjar Mausoleum. There are some suggestions this was a library, but to me i looks a little low in the ground for that??

Piled up bricks suporting a flimsy roof in one of the buildings anciliary to the Ahmad Sanjar Mausoleum.

The site of Merv today is flat, barren desert. When the cities were inhabited the whole area was much more fertile. Because it is so flat, you cannot raise your head without seeing yet another of the ancient sites within Merv. Here we see part of the ancient city wall at Gyaur-Kala, which comprised the city of Margian Antioquia founded by the Seleukid King Antiochus Soter [280-261 BC]. It is sited to the north of Ancient Merv.

A group of tourists on top of one of the towers of Erk-Kala. Called Margush for some time, this monumental relic from the 6th century BC covers about 50 acres.

Over 2,500 years old the enormous expanse of the Erk-Kala: the fortress area is about 50 acres with a massive circular wall without an obvious entrance. The entrance was actually located on a hill on the southern side of the fortress. You can see in front of you slightly to the right, the former King’s Palace.

A view of the Sultan Ahmad Sanjar Mausoleum from the top of the Erk-Kala.

Over time to faclititate movement, cuttings have been made in the fortress wall – here you can see the huge blocks of stone that made up the wall’s construction

A closer view of the remains of the former King’s Palace with the Erk-Kala Fortress in Ancient Merv.

In the 1950s a Russian Architect named M.E.Masson found the remains of a Nestorian Church with 33 rooms within the walls of the later fortress called Gyaur Kala built in the 3rd century BC. After the excavation the whole site was reburied in order to preserve it.

Similarly during excavations in the 1950s the remains of a Buddhist Stupa were found within the walls of Gyaur Kala. Many relics were found in the Stupa including a wonderful vase now simply called ‘The Merv Vase’ decorated with scenes from the life of the times. Also found was the clay head from a statue of the Buddha which would have stood 11 feet high. This site also revealed much new information about the history of Merv. As with the Nestorian Church the Stupa was reburied after it was excavated, in order to protect it. In the pic the trees and bush coloured green and mauve indicate the location of the stupa.

This shot shows you the remains of the walls of Gyaur Kala and in particular shows the large number of towers that were originally built on the walls – each of the mounds on the wall represent a former tower.

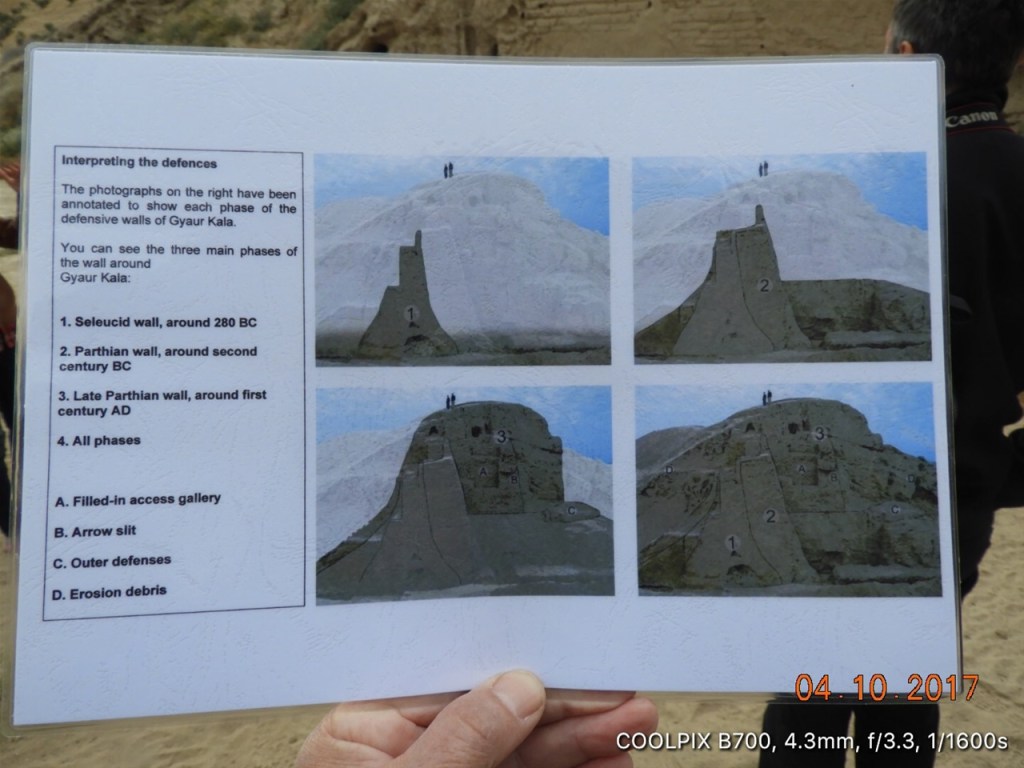

This is one of the gaps cut in the walls surrounding Gyaur Kala. What makes it especially interesting is that you can see the various phases showing the wall when first built and the subsequent additions to make it more secure….

….this is the visual aid used by our guide to illustrate what can be learned about the building of the wall by studying carefully this gap. Well worth a read and then compare with the pics that follow….

Here we can see the original Seleucid wall built around 280 BC and the Parthian additions made around 200 BC. We can then see towards the top the Later Parthian Wall added around the 1st century AD. The holes in the strutures show where beams – long since rotted – would have been located.

Here we see the filled in gallery that had originally run along inside the later Parthian Wall.

Moslems continue to bury their dead within Ancient Merv. Here you can see ancient and modern graves, side by side…..

An ancient sardoba [water reservoir] within Merv, my pic is not good enough for you to be able to see the water, but it is there…!

A side view of the well, you can see the tunnel down to the surface of the water and the islamic dome that has been constructed over the well itself.

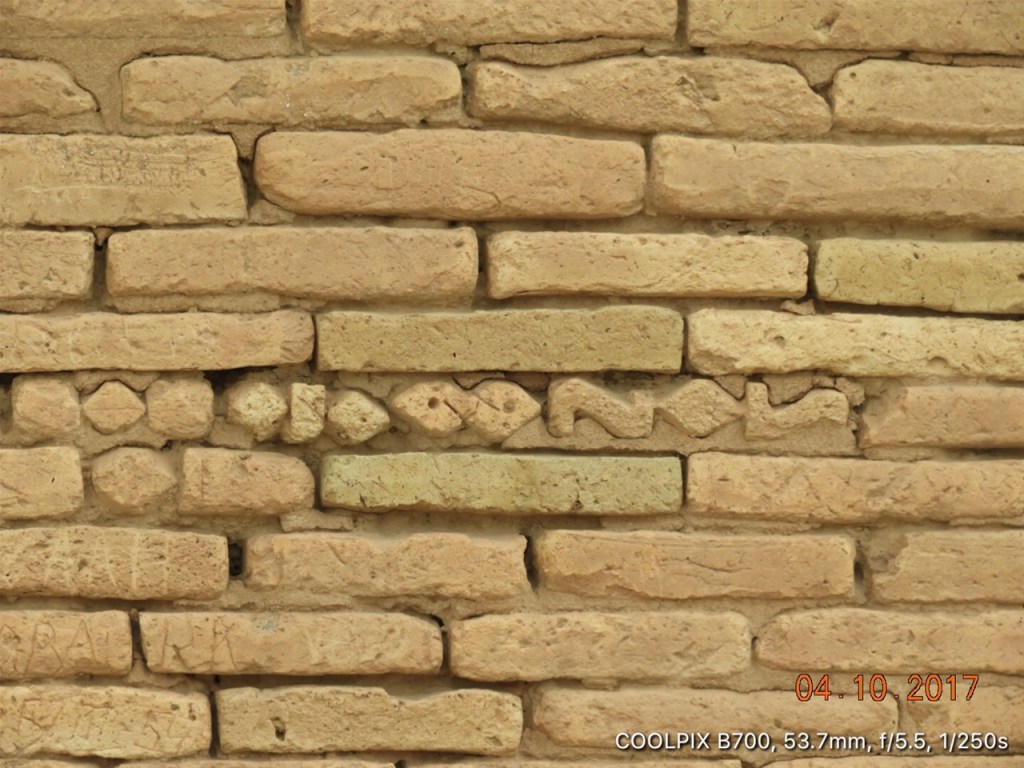

Some ancient decorations on the wall of the well. During the course of restoration most the well was reconstructed but where possible original materials have been brought in as shown here.

This shows you ancient decorations from the front of the sardoba at Merv.

Great Kyz Kala is a gigantic early medieval building at Ancient Merv, built in the 6th-7th centuries AD along with Little Kyz Kala. The walls are built of mud brick. Archiologists believe they belonged to a rich landowner who possessed a number of similar ‘castles’ which stretched along the Khurmuzfarra Canal north for about 30 kms.

Another shot to give you an idea of the momunental scale of these buildings. Although built in the 7th century they were still in use by the Seljuq Sultans 600 years later, as function rooms. Great Kyz-Kala is 150 feet long and 125 feet wide. There is pretty much no consensus amongst archaeologists as why the corrugated walls are built in that fashion.

Little Kyz-Kala located a couple of hundred yards due south of its big brother. It has more modest dimensions having a footprint 65 feet square and is in a much less well preserved state, except that some of its internal rooms and stairways are still discernable.

One of the rooms still evident inside Litle Kyz Kala at Ancient Merv

The remnants of a stairway within Little Kyz Kala at Ancient Merv

Another shot of Great Kyz Kala: you can see the draining pipes where restorers are striving to protect the remains of this gigantic 1,500 year old mud brick edifice

Taken from the top of Little Kyz Kala this shows you the desert scrub all across Merv. Elements of the ancient canals do still remain and they are responsible for the relatively fertile look of some parts of the place…

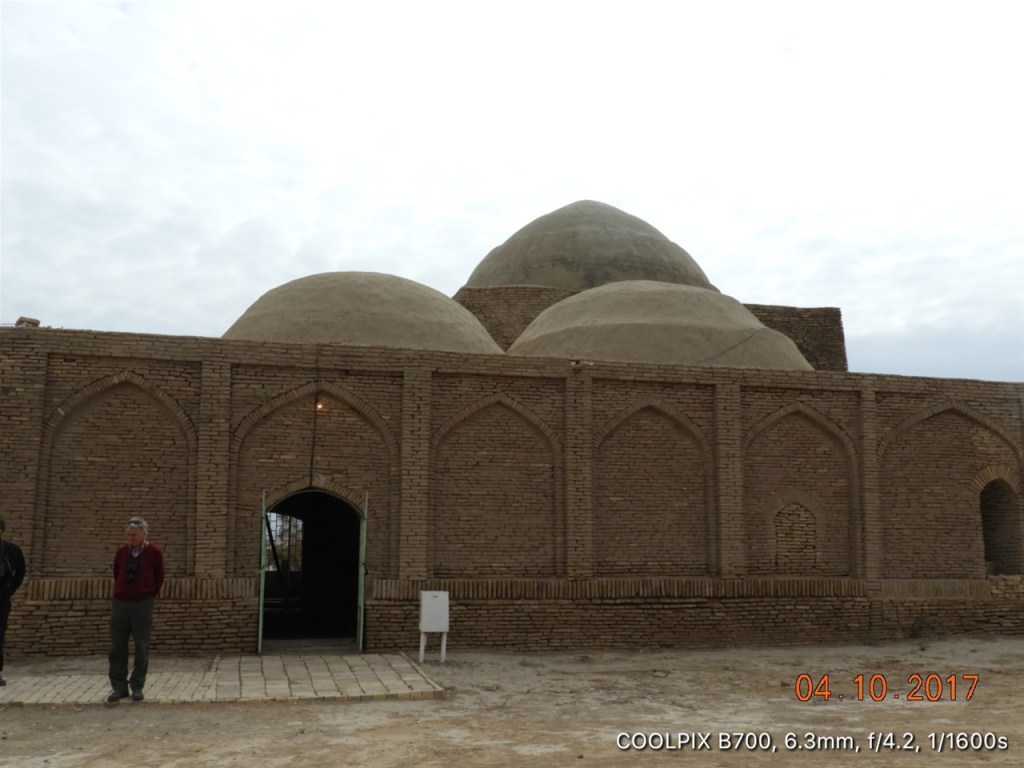

The Mausoleum of Muhammad ibn Zayd on the banks of the Khurmuzfarrah Canal. Muhammad ibn Zayd was a fifth generation descendent of the Prophet. The Mausoleum was built 400 years after the death of Muhammad ibn Zayd, above the tomb in which he was buried.

On this tree female Moslem pilgrims to the tomb of Muhammad ibn Zayd leave strips of cloth torn from their clothing: this is a Moslem tradition that we saw at other shrines and tombs in this part of the world.

The brick built internal cupola of the dome of the Mausoleum of Muhammad ibn Zayd

This pillar looks like a long ago attempt to support the arch inside the Mausoleum of Muhammad ibn Zayd.

Some archaeologists believe that Muhammad ibn Zayd lived in a ‘splendid’ khoshk [fort] located slightly to the east of the mausoleum. Today all that remains is an enormous 7th century mound from which this pic of the mausoleum was taken.

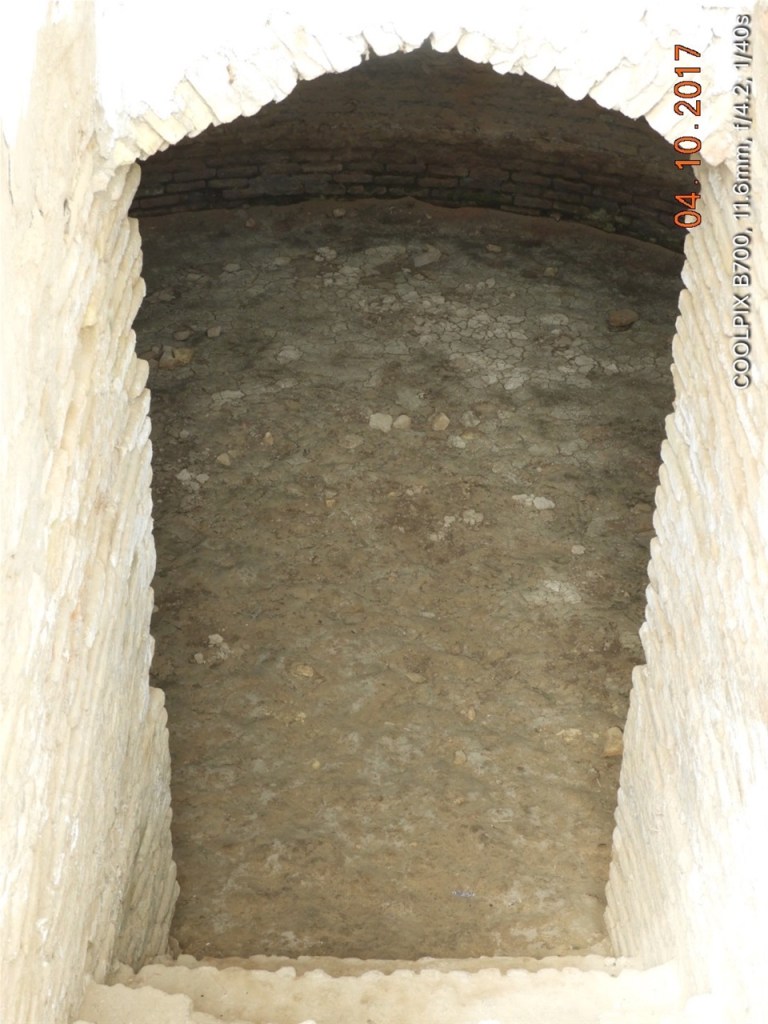

In the gardens around the Mausoleum of Muhammad ibn Zayd there is another sardoba [water cistern]. This one no longer has any water in it….

The cistern was evidently built at the same time as the mausoleum and water appears to have been carried to it from the Khurmuzfarra Canal not far away through a series of pottery pipes.